An in-depth analysis of DDP Yoga

"It ain't your mama's yoga," but it does have clear roots and influences in the other fitness programs throughout history

In her study, "Branding Yoga: The Cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga,” Dr. Andrea Jain explored the transition of yoga from a counterculture fitness trend to mainstream cash cow. Ultimately, she concludes yoga’s entrance into the mainstream was spearheaded by the entrepreneurial efforts of three key figures: B.K.S. Iyengar, Swami Muktananda, and John Friend. While these, of course, were not the only men to develop yoga programs of their own, they were key figures in defining the movement. Each program possesses its own nuances in its approach to yoga. Iyengar Yoga’s focus, for instance, is more centered around postural and soteriological movements and breathing, whereas Muktananda’s Siddha Yoga devised a more spiritually-rooted experience (Jain). Friend, who came some time later, blended elements from both Iyengar and Siddha Yoga, having studied both programs before creating Anusara Yoga. But just as John Friend borrowed from his predecessors, a man named Diamond Dallas Page, real name Page Falkinberg, would later borrow from him.

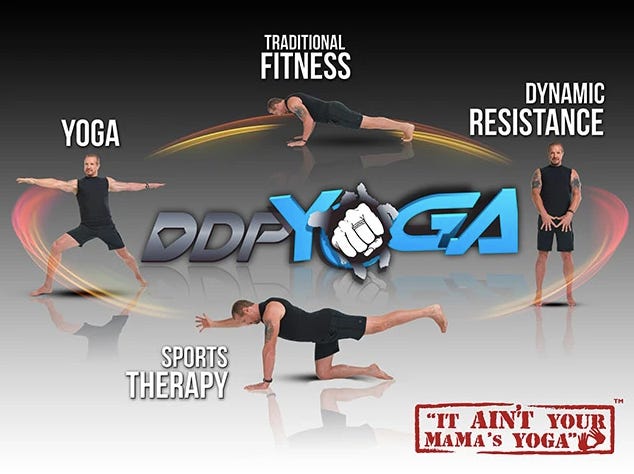

Just after the turn of the century, while Friend’s yoga empire was still riding high, another man, wrestling Hall of Famer Diamond Dallas Page, launched his own yoga brand. For his program, which would come to be known as DDP Yoga, Page adopted some of the postural poses and movements found in Iyengar Yoga, adding in a healthy dose of Friend’s infectious positivity. What he didn’t borrow from Jain’s influential yoga entrepreneurs was Shiddha Yoga’s spiritual teachings, stating his program was more about the workout than the “spiritual mumbo-jumbo” (Page, p. 128). “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.”

Having followed Page’s wrestling career and hearing of how he’d rescued and rehabilitated fellow legends like Jake “The Snake” Roberts and Scott Hall from severe substance abuse issues, I decided to give his program a shot and see what it was all about.

More than just the program’s workouts, in writing this analysis, I wanted to consider its culture and surrounding elements as well. Is it adequately inclusive of minority groups with representation among its membership, marketing campaigns, and instructor program? I wanted to know. What were Page’s personal influences not just in designing the program but in shaping his own persona?

As Natalia Petrzela detailed in her study, “The Siren Song of Yoga,” yoga developed a “whiteness” problem over time despite its Southeast Asian origins and the Neo-Hindu gurus who popularized in the west (Petrzela, p. 392). Anusha Wijeyakumar explored this in the present day in her InStyle piece titled “We Need to Talk about the Rise of White Supremacy in Yoga.” The radical right-wing conspiracy group QAnon has worked to infiltrate many yoga programs and practices in recent years through “vaccine skeptics, natural health fans and concerned suburban moms,” the piece states, citing Kevin Roose of the New York Times (Wijeyakumar). Thankfully, I’ve seen nothing anti-vax or QAnon related throughout my time participating in and following the program. If I had, I might have struggled to separate the workouts, as beneficial as they are, from the conspiracy nonsense and misinformation.

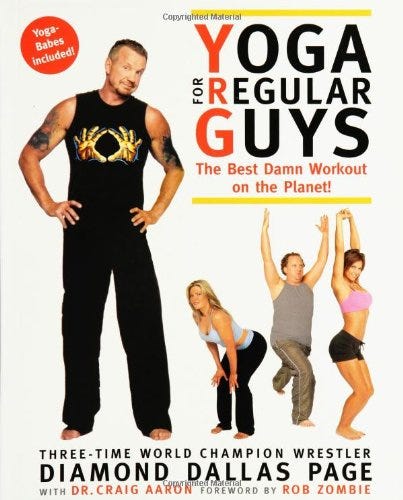

When DDP Yoga first launched, it was known as "Yoga for Regular Guys" (YRG) and stumbled out of the blocks. The program, which Page developed in his early 40s as a means of rescuing his wrestling career from a severe back injury, professed to blend elements of traditional yoga with old-school calisthenics and physical rehabilitation techniques, the result of which was a “yoga workout” perfectly suited for men. Why men, specifically? Page explains in his book, Positively Unstoppable: The Art of Owning It, his initial resistance to the practice was due to yoga not being “manly,” stating to his then-wife, Kimberly “[Eff] that. I ain’t doing yoga” (Page, p. 124) when she encouraged him to give it a chance amid his initial recovery. This apparent sentiment would stick with Page, even after adopting a yoga routine of his own and modifying it with rehab exercises. Despite his unexpected return to the ring and the best years of his career following thereafter, he remained cognizant of yoga’s perception among men, particularly “macho” men, the kind you’d imagine finding in a locker room full of professional wrestlers in the 1990s.

In an effort to market his yoga program toward "regular guys," the program and its vernacular were filled with innuendo and crude humor (Page, p. 131), an apparent attempt to reinforce hetero-normative behavior, as seen with Arnold Schwarzenegger in the docudrama, Pumping Iron (Butler and Fiore). Over time, it became apparent that YRG would need to cast a wider net regarding a target audience, and a rebrand centered around Page and his existing celebrity proved to be the answer. The result, despite Page's resistance to his program being called "yoga" was DDP Yoga.

“From a guy who wouldn’t be caught dead doing YOGA, to having my name beside it—now that is being flexible…and it’s kind of hilarious!” (Page, p. xv).

As part of the rebrand, DDP Yoga altered its workouts and “cleaned up” its casual vernacular –though certain moves do still harken back to their original names. This is perhaps best seen in a movement now called "MSM," in which one goes from a downward dog position into a plank and then drops their hips and sways gently to stretch the lower back. "MSM," incidentally, is shorthand for the original name: "Miss You So Much.” And then there’s this gem from a video he produced with Big Think in 2014:

“Most yoga is ‘Namaste.’ DDP Yoga is T&A: Tone and Attitude” (Don’t call it yoga, brother, bigthink).

Between the more inclusive approach and incredible success stories like Arthur Boorman’s (dallaspage), the program picked up a great deal of momentum, including from the very "yogis" Page had originally been dismissive of. Once they were on board, however, the company began a secondary "soft" rebrand, in which DDP Yoga became commonly referred to as simply "DDPY."

“The truth is that DDP Yoga hardly resembles traditional yoga, and that’s part of the reason why I now brand it DDPY. Yoga played a huge role in its genesis and development, but I am a big believer in moving beyond tradition and thinking outside of the box” (Page, p. xvi).

There’s no question DDP Yoga has branded itself as a unique program that is separate from traditional yoga practices, even if its marketing has altered and self-corrected over the course of 16 years. Similar to Friend, Page speaks with great positivity and energy as he leads each workout. His charisma is unmistakable. Behind him, his instructors are composed of the program’s success stories, including Boorman. At the beginning of each workout, each instructor is introduced not just by name but by how much weight they’ve lost through DDPY. Women also mention—some upfront, some when directly asked by Page—the reduction in their dress size as well.

In the workouts themselves, Page makes a point to not only share but demonstrate, be it himself or through one of the instructors behind him, “modifiers” for each move or pose. This is a clear, and helpful, effort to make the workouts more accessible to individuals who, whether due to a previous injury, ailment, or weight issues cannot perform the moves as intended. What’s more, the program has developed workouts on everything from waking up and getting out of bed to chair-assisted exercises, creating a bridge for just about anybody to participate in the program.

I did notice when first beginning the program that each of Page’s instructors were also white, though there was a good mix of men and women. Aside from one other former professional wrestler, Stevie Richards, everyone else is an ordinary person. The women might be wearing yoga pants and tank tops but they aren’t obscenely spotlighted while doing squats or bending over like the workout videos of old, and the men look to be wearing mostly official DDPY-branded gear or basic shorts and t-shirts you’d find at a Kohl’s or Old Navy.

A glance at the online community in the message boards and Facebook groups suggests the membership is predominantly white as well, though there are members from other minority groups as well. One particular champion of DDPY, a man named Bryan, has been featured by DDP Yoga’s Twitter and Instagram accounts recently for his veracious activity in the brand’s online community and his impressive transformation, which saw him go from 390 pounds in August of 2019 to just 216 pounds today. It’s probably unfair to suggest that spotlighting Bryan, a black man, is at least partially motivated by a desire to help market to other black consumers, thereby tokenizing him in the process, but of the success stories they’ve shared, he does appear to be a bit of an outlier.

In my personal experience with DDPY, which began in earnest in early February of 2021, I found the workouts to be incredibly engaging yet accessible. The app is free to download and includes a trial period that can range from a week to a month depending on the time of year. Membership costs just $8 per month, and frequent specials allow you to save additional money if you sign up for an entire year upfront. Equipment is optional, but I like to just use a yoga mat and Bluetooth heart monitor, which I purchased from DDPY for $49.99. For people with hearing impediments, closed captioning is provided for each video, though it must be activated manually at the start of each workout.

Unlike workouts like CrossFit, the exercises are low-impact and strengthen not just muscles but ligaments and tendons as well, and good grief can they leave you, as Page often jokes, “sweatin’ and swearin.’” In the first six months, I dropped over 54 pounds and got down to my lowest weight since my sophomore year of high school. To be fair, I’ve worked out every day, rather than the three or four days per week suggested by the proposed schedule. Along the way, I’ve had some strains and general soreness, but nothing so debilitating that I was forced to take time off for an extended period.

The basis of DDPY is built on dynamic resistance, which harkens back to Charles Atlas and his “dynamic tension” (“Give me your measurements and I’ll prove that you can have a body like mine!”). Page, however, credits this inspiration to Bruce Lee, who was in tremendous physical condition despite never doing weight training. By engaging the major muscles in your legs, arms, and chest, you force your heart to pump faster, sending blood to the flexed muscles. This, in turn, moves your heart into an ideal “fat-burning zone,” which is calculated for a person based on the following formula: 180 – Your Age = Top of your zone. Top of your zone – 20 = Bottom of your zone (Page, p. 157). The goal is to remain in the fat-burning zone for as much of the workout as possible. Should you go into the “red zone”, the app will display a message instructing you to either “disengage” the tension in your muscles or go into “safety zone,” which is a resting, fetal-like position that quickly lowers your heart rate.

While there is a fair bit of stretching, the beginner, intermediate, and advanced portions of the program offer limited “pretzeling” of one’s anatomy like some other yoga programs have a tendency to do. Instead, the stretches are relatively simple, utilizing dynamic resistance as you transition from one move to the next, and then incorporating push-ups, crunches, and squats, as well as the occasional physical rehabilitation exercise into the mix. Along the way, you improve upon not just your more traditional strength like your arms, chest, and shoulders, but your flexibility and core strength as well.

The program is heavily marketed on its ability to help people lose weight but, from what I’ve seen, it doesn’t profess to be a “one-stop shop” whose workouts alone will magically help people drop excess weight. The program includes a nutritional program free of cost, in which Page and his wife prepare gluten-free, non-dairy meals developed by nutritional experts. This section of the app includes tons of videos for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, as well as snacks and even desserts. While I haven’t tried any of these recipes, I appreciate knowing they’re there.

While yoga wasn’t always destined to become a female-centric fitness practice, the bodybuilding movement and presentation of the “ideal man” shifted to become more musclebound and chiseled, like Arnold Schwarzenegger in the late 1970s. This, I believe, left yoga and its less strenuous, more stretching and toning-based practices to occupy a more feminine space within the US fitness scene. DDP, having been a big, muscly professional wrestler at the height of the industry’s boom period, felt that same apprehension of yoga when he first approached it. It wasn’t considered “manly,” and doing it, even in the privacy of his own basement, was not something he took to lightly. It wasn’t until yoga essentially saved his career that he began to change his viewpoint of it, and even then his marketing strategies and rebranding efforts make it clear he still harbors concerns over how widely accepted yoga would be by men today. This was notably apparent during a 2014 video with Big Think titled “Don’t call it yoga, brother.”

“I never even let people call DDP Yoga yoga. People come up to me all the time at autograph signings or personal appearances I’m doing and they’re all excited. ‘DDP, oh my God, I’ve lost 60 pounds. I love your yoga!’ There’s a big group of people around. I go, “What did you call it?” (“Don’t call it yoga, brother,” bigthink).

In his book, Page stated that while he had to embrace some of the more traditional yoga elements amid the rebrand, he wanted to be seen as the “anti-yogi yogi” (Page, p. 130). While this would seemingly present a “bad boy of yoga” image, Page’s demeanor instead radiates a warm, friendly vibe in both workouts and his Motivational Monday videos he posts weekly. In his book, he lists Tony Robins as a major influence and, listening to DDP speak, it’s not hard to recognize. As it relates to other fitness figures of the past, while he does talk at times about toning and sculpting muscle, he avoids going the full Jack LaLanne route by commenting on peoples’ “ugly fat” or insisting certain moves target regional fat (jacklalanneofficial), which isn’t possible in the first place.

Whether or not you classify DDPY as yoga—and if you do, don’t tell him—what cannot be disputed is the results the program capable of producing. Page likes to say “It works, so long as you do.” In my case, as well as the success stories I’ve observed, I can attest to that.

I approached DDPY after years of back problems stemming from a severely herniated disc. The injury had continually kept me from participating in other fitness programs like CrossFit. DDPY was the first program that not only helped me work around the injury but ultimately stabilize the region with core strength so that it was no longer a problem. As a result, I’ve managed to get into arguably the best shape of my adult life, something I didn’t think would be possible as recently as January. I don’t know how much of that is DDP’s charisma and positivity, per se, but I can say his personality leaps through the screen, ever encouraging even as you curse his name to “shut up and count faster.”

References:

06, Anusha Wijeyakumar Oct, and Anusha Wijeyakumar. “We Need to Talk about the Rise of White Supremacy in Yoga.” InStyle, www.instyle.com/beauty/health-fitness/yoga-racism- white-supremacy.

Bigthink, director. Diamond Dallas Page: Don't Call It Yoga, Brother | Big Think. YouTube, YouTube, 3 Oct. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=aB5ys1zsz-o.

Butler, George and Robert Fiore, directors. Pumping Iron. Pumping Iron, 1977.

Charles Atlas. “Give Me Your Measurements and I'll Prove You Can Have a Body like Mine!” Popular Mechanics, vol. 54, no. 3, 30 Sept. 1930, p. 41.

Jacklalanneofficial, director. YouTube, YouTube, 20 May 2013, www.youtube.com/watch? v=y4A3mdG5zbQ.

Jain, Andrea. “Branding Yoga: The Cases of Iyengar Yoga, Siddha Yoga and Anusara Yoga.” Approaching Religion, vol. 2, no. 2, 2012, pp. 3–17., doi:10.30664/ar.67499. Petrzela, Natalia Mehlman. “‘The Siren Song of Yoga.’” Pacific Historical Review, vol. 89, no. 3, 2020, pp. 379–401., doi:10.1525/phr.2020.89.3.379.

Dallapage, director. YouTube, YouTube, 30 Apr. 2012, www.youtube.com/watch? v=qX9FSZJu448&t=37s.

Page, Diamond Dallas. Positively Unstoppable: The Art of Owning It. Rodale, 2019.